How Biometrics Can Help Democracies Build Trustworthy Elections

The number of democracies in the world is going down. Many countries are walking a fine line between democracy and autocracy. Even in long-established Western democracies, worries about election results being challenged are becoming more common.

Building trust in elections takes strong political and social efforts. But in many cases, biometric technology can be a big help in making voting more secure and reliable.

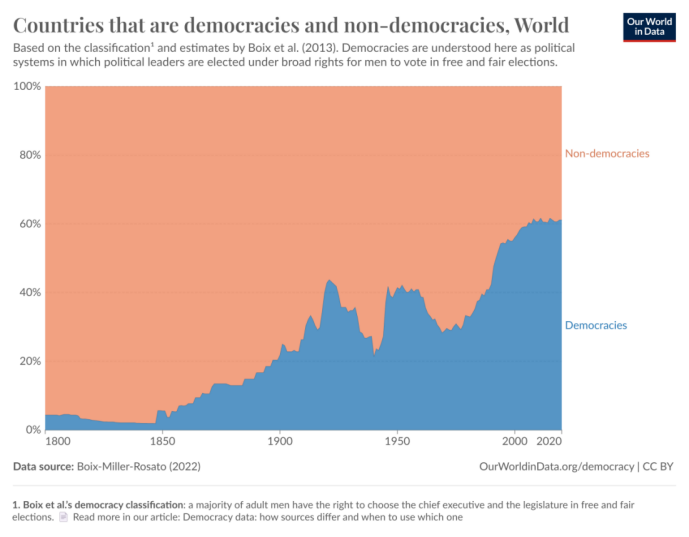

Most countries around the world are democracies today, and billions of people enjoy basic democratic rights like the right to vote and the freedom to speak their minds. There’s no doubt that democracy has been a huge success for humanity. But if we rewind just 200 years – back to the time when French revolutionaries were storming the Bastille, demanding liberty, equality, and fraternity – the world looked very different. Modern democracies were just beginning to take shape, and nearly everyone around the globe still lacked these basic rights.

How many countries are democratic?

According to Our World in Data, a project overseen by the University of Oxford, based on academic research and classifications, in 2021 around 60% of the world’s countries were democracies.

Source: Our World in Data. Retrieved in November 2022.

Is Democracy on the Decline Worldwide?

The number of people who don’t have democratic rights is higher than ever—mainly because the world’s population is growing faster than democracy is spreading. The journey to democracy is often complicated and inconsistent. Take Tunisia, for example. It became a democracy in 2012 and was seen as the only real success story from the Arab Spring—the wave of pro-democracy protests that swept across the Middle East and North Africa in the 2010s. But by 2022, the ongoing power struggle between Tunisia’s president and its parliament has put the country’s democracy under serious pressure.

India is the world’s largest democracy, with nearly 1.4 billion people. When the country democratized in the 1950s, it extended civil rights to a significant portion of the global population. However, in 2019, the V-Dem Institute – an independent research group from Sweden – labeled India as an “electoral autocracy.” Now, many are questioning what the future of democracy in India will be.

“The total number of people who are not granted democratic rights is higher than ever – simply because the world’s population grows faster than democracy spreads.“

Even in countries with long-standing democratic systems, internal groups are starting to take advantage of the system’s weaknesses, putting democracy at risk. In the United States, after Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election, then-President Donald Trump spread multiple false claims, insisting the election was stolen from him through rigged voting machines and electoral fraud His efforts to overturn the 2020 elections culminated in what is now considered the darkest day for democracy in USA: the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol.

Concerns that political parties might reject election results cast a shadow over major elections in 2022, including Brazil’s presidential election and the U.S. midterms. Looking ahead, democracy no longer feels like something guaranteed or universal. Instead, it seems more like a fragile achievement that needs care and protection.

Why Are Voter Registers So Important?

Flawed voter rolls – with issues like:

- Duplicate names

- Outdated information

- Missing names

These problems can:

- Open the door for manipulation

- Undermine citizens’ trust in the election process

- Allow political parties to cast doubt on the results

- Prevent many citizens from voting, impacting the fairness of the outcome

To be a strong democracy, it’s crucial to have:

- Reliable and accurate voter registration processes

Trust is the heart of every democracy.

Every democratic country’s political system has been shaped by its people over decades, sometimes even centuries. But at the heart of every democracy is one simple truth: the people take part in decision-making. This can happen directly in what’s known as a direct democracy, but more often, it’s done through elections where people choose representatives to make decisions for them.

Trustworthy elections are the foundation of any democracy. If citizens don’t trust the election process, they’re likely to doubt everything else their government does. With more frequent disputes over election results and claims of voter fraud, it’s clear that trust is a key part of democracy. This means elections not only need to be fair and equal but must also feel trustworthy to the public.

It’s a big challenge that all democracies—whether new or long-established—are now facing. So, can technology offer a solution?

How Biometrics Has Made a Difference

Building trust in elections takes time—it’s a long-term political and social process that doesn’t happen overnight. But sometimes, technology can step in and help out.

In the early 2000s, many countries began turning to biometrics to create more accurate voter lists. This helped governments overcome political crises, strengthen new democratic institutions, and, in some cases, simply speed up the voting process.

A good example of this comes from Bangladesh. In 2007, parliamentary elections were postponed after weeks of political unrest. A coalition of political parties even threatened to boycott the election, with one of the main issues being the poor quality of the voter rolls. The list had over 14 million errors and fake names—an astonishing number, considering there were about 80 million voters at the time.

Under growing pressure to ensure fairer elections, the electoral commission decided to use biometrics to build a new, more reliable voter register. Biometric Voter Registration – often called BVR – It’s actually one of the most common ways biometrics is used in elections. Biometric data, like fingerprints or facial scans, is collected for each eligible voter using special registration kits. This information is then stored in the voter register along with other personal details. This helps quickly spot duplicate names and keeps the voter lists accurate and consistent.

What kind of data is collected through Biometric Voter Registration?

Some countries, like India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, only collect photos, while others stick to just fingerprint scans. Many nations, such as Mexico, Nigeria, and Mozambique, gather both. Brazil takes it a step further by also collecting signatures.

“Observers from the International Republican Institute assessed that the Bangladeshi election based on Biometric Voter Registration was the ‘best election in the country’s history’.”

It was a significant moment. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) teamed up with the Electoral Commission in Bangladesh to gather the resources needed for a bold project. They distributed over 1,000 webcams and fingerprint scanners throughout the country, and within just 11 months, the commission successfully registered 80.5 million voters.

The following year, in December 2008, Bangladesh held its long-delayed parliamentary election. Observers from the International Republican Institute, a US-based non-profit focused on promoting democracy, called it the “best election in the country’s history.”

In Ghana, using biometric voter identification resulted in the highest voter turnout ever recorded.

In Bangladesh, for example, biometric technology helped solve a serious political crisis by making voter registration more accurate and trustworthy. Many other countries are now turning to biometrics to create their voter lists, especially in places where people don’t have reliable ID documents or where existing population records aren’t trusted enough for gathering voter information.

Biometrics can also be used on election day to confirm voters’ identities at polling stations, helping to prevent fraud, identity theft, and multiple voting. Ghana, for instance, used biometrics in its 2020 election to both create voter rolls and verify voters on election day.

How many countries use biometrics in their elections?

According to the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), 33% of the 177 countries surveyed collect biometric data as part of their voter registration process. Meanwhile, 30% use this data to identify voters at polling stations.

In most cases, biometric voter identification is done manually. This means a poll worker checks the voter’s appearance against a photo on a voter list. Only 9% of the countries surveyed use an electronic system, where a computer verifies the voter’s identity.

The Growing Use of Facial Biometrics in e-Government

In digitally advanced countries, biometric registers can improve e-Government services. Citizens can use apps to apply for IDs, renew driver’s licenses, or access visas, pensions, welfare, and health benefits using their biometric credentials.

While biometrics can strengthen democracy, it’s not enough on its own.

Since 2009, Bolivia has used biometric voter registration. This was crucial as it was the first election under the new constitution. Opposition parties had concerns about the old registry, so the electoral commission rebuilt it with biometrics.

The effort was massive: over 3,000 registration centers were set up, and more than 3,500 people were trained. In just 75 days, five million people were registered—setting a world record for speed.

International observers like the Carter Center noted that this helped restore trust in Bolivia’s election process.

“Bolivia set a world record in speed for setting up a voter registration. Five million people have been enrolled in the new Bolivian register, thanks to biometrics, in just 75 days.”

Bolivia has long been politically divided, and since 2019, the country has faced serious unrest. That year, claims of election fraud led to protests and the resignation of President Evo Morales. However, the biometric system wasn’t blamed, and the Organisation of American States found it generally reliable.

The path to democracy is rarely smooth. Building trust in elections takes time, effort, and cooperation. While biometrics can boost credibility, technology alone can’t fix deeper political and cultural issues—it’s just one tool among many to support democracy.